In the history of anime the director who is certainly the most famous and revered in the Western hemisphere is Hayao Miyazaki (Spirited Away, Princess Mononoke). He has made quite a few cracking films himself, and even film buffs have likely heard his name, at least in passing. There is already tons of coverage about the poster boy of Ghibli and many directors haven’t had quite the same exposure.

As someone who has been a fan of anime for a long time now, I have found it very fruitful to explore different directors and what they manage to bring to a project. There is always something beautiful and unique that many directors bring, whether it is their style of writing characters or telling stories, the techniques they employ, or the way they use animation’s limitless potential to present ideas and beliefs which live action simply can’t.

In this list, I will be covering my Top 5 Favourite Anime directors that aren’t Miyazaki-san, and are deserving of as much praise and recognition.

Osamu Dezaki

Osamu Dezaki, born on November 18th, 1943, started out as a manga artist at Toshiba, yeah, that Toshiba, they have their own manga division. His long career in anime began by working as an animator and episode director on Mushi Production series such as the first breakthrough anime TV series, Astro Boy (1963-1966) and Dororo (1969).

(Ashita no Joe 2, 1980-1981, TMS Entertainment)

He then became quite notable for his work on classic boxing drama Ashita no Joe (1970-1971), which lead to a second season that aired 9 years later. Dezaki was known as being the founder of the studio Madhouse (Death Note, Cardcaptor Sakura) and for being incredibly versatile in various genres, leading to an eclectic body of work. Such examples include pulpy film noir with Golgo 13 (1983), escapist space opera with Space Adventure Cobra (1982-1983), fantasy adventure with Gamba no Bouken (1975), medical thriller with the Black Jack OVA (1993-2011), and even did various films and specials for Lupin the Third and Hamtaro.

For many fans, Dezaki’s strongest work was with shoujo series such as Rose of Versailles (1979-1980), Aim for the Ace! (1973-1974), Dear Brother (1991-1992) and classic novel adaptations such as Treasure Island (1978- 1979) and Nobody’s Boy Remi (1977-1978). Many of his shows also contained character designs by Akio Sugino (Phoenix, La Seine no Hoshi), giving them a distinctive look.

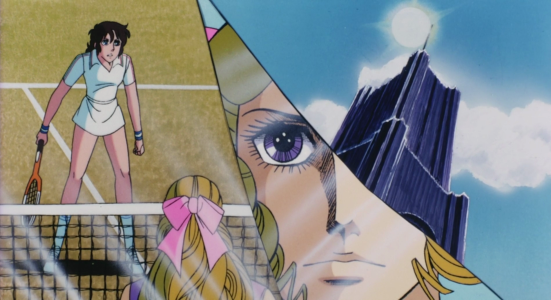

(Aim for the Ace! Movie, 1979, Madhouse)

Dezaki had a love of cinema and theatre which was clearly shown throughout his career, with strong usage of stark lighting similar to the work of Jean Pierre Melville, Hitchcockian Dutch angles, split screens akin to Brian De Palma, as well as triple takes and speed lines to enhance the impact of an exciting scene. Most famously, he invented an iconic technique known as “Harmony” or “Postcard Memories”. These were freeze-frames, interpolated as sketchy illustrations, designed as a cost cutting technique that were often saved for dramatic scenes or moments of great change in the characters. These techniques are still being used today, so you could say Dezaki helped the medium find its own identity and style.

(Rose of Versailles, 1979-1980, TMS Entertainment)

The combination of his stylistic techniques and his flair for melodrama gave Dezaki’s work a grandiose and theatrical quality that is still unmatched by any other director in the medium. He passed away at the age of 67 on April 17th, 2011 due to lung cancer, leaving behind an incredibly versatile and strong oeuvre of work, and his influence can be seen in directors like Akiyuki Shinbo (Puella Magi Madoka Magica, Bakemonogatari) and Hiroyuki Imaishi (Gurren Lagann, Kill La Kill).

Mamoru Oshii

Mamoru Oshii, born on August 8th, 1951 in Tokyo, is probably one of the most varied, versatile, fascinating and iconic directors in the history of anime. Starting off as an episode director on shows such as Belle and Sebastian (1981-1982), Ippatsu Kanta-kun (1977-1978) and Yatterman (1977-1979), he oversaw the first 106 episodes of the wacky sci-fi romantic comedy Urusei Yatsura (1981-1986), as well as the first two movies, Only You (1983) and Beautiful Dreamer (1984).

(Angel’s Egg, 1985, Studio DEEN)

A year later, he made the existentialist art-house film, Angel’s Egg (1985), which alongside Beautiful Dreamer, cemented him as a director unafraid to take risks. This isn’t surprising, considering his cinematic influences include European directors such as Michelangelo Antonioni (Blowup), Andrei Tarkovsky (Stalker, Solaris), Jean-Luc Godard (Breathless, Alphaville), Andrzej Munk (Man on the Tracks), Chris Marker (La Jetée), Federico Fellini (8½) and Ingmar Bergman (The Seventh Seal).

(Patlabor 2: The Movie, 1993, Production I.G)

He then founded the company HEADGEAR, and worked on Mobile Police Patlabor franchise, a mecha series mixed with police procedural elements that was also very heavily character driven. The franchise had various manga, novels, OVAs, TV shows and two theatrical films, both directed by Oshii. The success of the series led to Oshii working on the influential Ghost in the Shell (1995), which would eventually spawn a sequel released a decade later titled Innocence (2004). He has also created the Kerberos saga, which has lead to two live action films, manga, radio dramas and an anime film written by Oshii called Jin-Roh: The Wolf Brigade (1999).

Some common themes in his work are the exploration of society, government corruption, terrorism, identity, urban warfare, faith, technology, humanity and religion. This is further cemented by his motifs, including animals such as birds and Basset Hounds, reflections of mirrors, windows and water. Oshii usually includes ma (interval) montages, and moody atmospheric visuals set to haunting music by his frequent collaborator, Kenji Kawai (Ranma ½, The Irresponsible Captain Tylor).

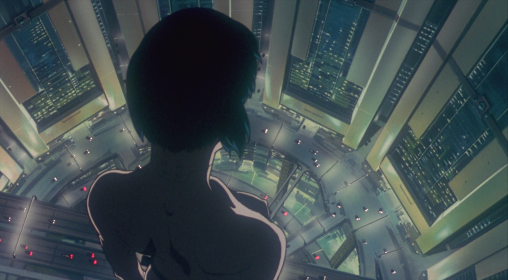

(Ghost in the Shell, 1995, Production I.G)

Oshii’s well known for working within science fiction and often explores profound subject matter in his work, coupled with challenging use of symbolism. While he has been known to influence directors like The Wachowski’s (The Matrix) and James Cameron (The Terminator), Oshii’s style is very much his own. He is known as the Stray Dog of anime for a reason, to the point that in a Johnathon Ross interview, he said that he thinks he’s a reincarnated Basset Hound. Maybe we will never know, but I’d like to think that.

Hideaki Anno

Hideaki Anno, born on May 22nd, 1960, grew up spending a lot of his free time exploring the arts, and during his time in Junior High School he attended the art club. In 1980, he attended the Osaka University of Arts, made friends with Hiroyuki Yamaga (Magical Shopping Arcade Abenobashi) and Takami Akai (Banner of the Stars), and made short films with them. On August 20th, 1983, a little after Anno dropped out of University, he made history by being the animation director on the infamous Daicon IV Opening Animation. This influential short film, considered a holy grail within anime fandom, gave Anno the opportunity to work as an animator on all-time classics like Macross: Do You Remember Love? (1984) and Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind (1984).

(Aim for the Top! Gunbuster, 1988-1989, GAINAX)

Anno, along with Yamaga and Akai, founded the legendary studio GAINAX in 1984. This lead him to become prolific in his field, working as an animator on works like Megazone 23 Part I (1985), The Wings of Honnêamise (1987), and Giant Robo: The Day the Earth Stood Still (1992-1998). In 1988, he made his directorial debut with the OVA series Aim for the Top! Gunbuster (1988-1989). This 6 episode mecha series became infamous for it’s heavy and emotionally charged ending.

After his experience on Nadia the Secret of Blue Water (1990-1991) Anno became very depressed as a result of interference from NHK. This lead to the creation of the iconic TV series, Neon Genesis Evangelion (1995-1996). The series is well reknown for utilising the super-robot anime framework to explore themes such as depression, loneliness, identity and existence often with heavy psychoanalysis of the characters. The show’s success lead to a follow-up film titled The End of Evangelion (1997), which was both incredibly nihilistic and surreal.

(Neon Genesis Evangelion, 1995-1996, GAINAX)

Anno was one of the first directors in anime who proclaimed to be an otaku (obsessed fan), meaning his work is not only influenced by but also directly references other anime, manga and pop culture. This includes creators such as Yoshiyuki Tomino (Space Runaway Ideon, Mobile Suit Gundam), Stanley Kubrick (A Clockwork Orange, 2001: A Space Odyssey), Go Nagai (Devilman, Mazinger Z), Gerry Anderson (UFO, Thunderbirds) and Kihachi Okamoto (Battle of Okinawa), in addition to tokusatsu and kaiju icons Ultraman and Godzilla.

Anno is perhaps best known for creating works that explore the human condition, with Evangelion and Kare Kano focusing on characters who are forced to question their place in life and society, their vulnerability and having to face overwhelming pressure, reflecting on the director’s personal experience. He uses cinematic techniques, such as stroboscopic montages, static long cuts that create an uneasy sense of tension and introspective, philosophical dialogue. Anno then combines this with cost saving avant-gardt techniques, such as the use of incomplete storyboards and simple text frames to ask questions to the character and viewer alike. He sometimes even throws in live action footage to often surreal and otherworldly effect.

(The Wing of Honneamise, 1987, GAINAX)

Thanks to a prime focus on characterization, coupled with a willingness to take risks by playing with various techniques and styles of storytelling gives Anno’s work a personal touch that makes his work incredibly fascinating and memorable.

Masaaki Yuasa

Masaaki Yuasa, born on March 16th, 1965, is one of the most extraordinarily unique and visionary auteurs in modern anime. Throughout his career, he has worked as an animator on works ranging from Esper Mami (1987-1989), Chibi Maruko-chan (1990-1993), episodes and many of the movies of Crayon Shin-Chan, Noiseman Sound Insect (1997), Agent Aika (1997-1999), My Neighbours the Yamadas (1999) and Samurai Champloo (2004-2005).

(Mind Game, 2004, Studio 4°C)

Besides being an incredibly versatile animator, Yuasa also penned the screenplay of the incredibly trippy OVA Cat Soup (2001), and would eventually become a director starting off with his first feature length film Mind Game (2004). Based on a manga by Robin Nishi and produced by Studio 4°C (Tekkonkinkreet, Memories), the film was lauded for having a dynamic utilization of various animation styles and a story featuring inspiring themes about living life to the fullest coupled with quirky humour and characters. The film soon caught the attention of directors such as Satoshi Kon (Paprika, Millennium Actress), Mamoru Hosoda (Digimon Adventure: Our War Game, Wolf Children), Bill Plympton (The Tune, Cheatin’) and even psychedelic artist, Keiichi Tanaami (Oh! Yoko).

Over the past decade, working as a freelancer, Yuasa has directed the body horror series Kemonozume (2006), the Happy Machine segment of Genius Party (2007), thought provoking sci fi series Kaiba (2008), surreal dark comedy The Tatami Galaxy (2010), the Kickstarter backed short film Kick-Heart (2013), and the sports drama Ping Pong the Animation (2014).

(Kick Heart, 2013, Production I.G)

After establishing the studio Science Saru with his affiliate EunYoung Choi (Black Lagoon, Casshern Sins) Yuasa directed the Space Dandy (2014) episode “Slow and Steady Wins the Race, Baby” and in his first international collaboration, the Adventure Time episode “Food Chain”. He is currently busy with two feature length films due out this year with Night is Short, Walk on Girl and Lu over the Wall, and will be directing the newest adaptation of Go Nagai’s iconic manga, Devilman: crybaby, which will be airing in 2018 on Netflix.

(The Tatami Galaxy, 2010, Madhouse)

He has been inspired by animators such as Tex Avery (Red Hot Riding Hood, Blitz Wolf), Ladislas Starevich (Tale of the Fox), Rene Laloux (Fantastic Planet, La Maîtres du Temps) and Nick Park (The Wrong Trousers, Chicken Run), as well as the film Yellow Submarine (1968). One of Yuasa’s traits is that his animation plays with style, form and technique, giving his work an incredibly post-modern touch. One shot could be high in detail, the next could be rotoscoped, the next shot could be zany and loose. His work often includes existentialist themes and content, which in addition to the off-beat and unique playing with animation styles has a quirky approach and refreshing feel that allows Yuasa’s work to stand out, even within anime. Here’s hoping that Yuasa continues to create many wonderfully wacky and oddball shows and films for years to come.

Isao Takahata

Isao Takahata, born on June 29th, 1935, has had a long career working in the medium, and has worked in a variety of genres and styles, leading to a unique body of work.

After seeing the original cut of the French animated masterpiece, The King and the Mockingbird (1952 & 1980), Takahata became entranced with the possibilities of what animation could achieve. His beginnings at Toei Animation (Dragon Ball, Sailor Moon) were certainly humble, working as an assistant director on The Littlest Warrior (1961) and The Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon (1962), and was an episode director on Ken the Wolf Boy (1963-1965). His feature length directorial debut was the fantasy adventure film Horus, Prince of the Sun (1968), where he would become lifelong friends with anime legends Hayao Miyazaki and Yasuo Otsuka (Panda and the Magic Serpent, Animal Treasure Island).

(The Tale of the Princess Kaguya, 2013, Studio Ghibli)

After doing work on Himitsu no Akko-chan (1969-1970) and Mōretsu Atarō (1969-1970), he co-directed alongside Miyazaki episodes 13-23 of Lupin the Third (1971-1972). He would then oversee both Panda! Go, Panda! short films (1972-1973), as well as directing classic World Masterpiece Theater TV shows like Heidi, Girl of the Alps (1974), 3000 Leagues in Search of Mother (1976) and Anne of Green Gables (1979).

(Grave of the Fireflies, 1988, Studio Ghibli)

In the early 80s, he directed the slice of life comedy Chie the Brat (1981) and music themed fantasy film Goshu the Cellist (1982), all before becoming the co-founder of Studio Ghibli in 1985. After producing Nausicaa (1984) and Laputa: Castle in the Sky (1986), he would go on to direct the poignant semibiographical drama, Grave of the Fireflies (1988), the nostalgic and lyrical Only Yesterday (1991), the environmentalist fantasy comedy Pom Poko (1994) and the creative and heartwarming comedy My Neighbours the Yamadas (1999). 14 years later, after he struggled for a long time trying to get it made, Takahata released the beautifully emotional Tale of Princess Kaguya (2013), an adaptation of the classic Japanese folk tale, The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter.

Paku-san, as Miyazaki calls Takahata, has been influenced by Italian neorealism, French New Wave, Frederic Back (The Man Who Planted Trees), Yuri Norstein (Hedgehog in the Fog), Kenji Miyazawa (Night on the Galactic Railroad), Bertolt Brecht (The Threepenny Opera) and Yasujiro Ozu (Tokyo Story, Late Spring). Takahata’s work often deals with small, character driven stories that deal with melancholy, childhood, loneliness, emotion and tends to focus on relatable, mundane situations that are reflective, contemplative and riveting to witness.

(Only Yesterday, 1991, Studio Ghibli)

Through the power of animation, Takahata conveys metaphor and plays with different visual lenses to symbolically represent the state of the character’s mind and feelings. In Only Yesterday, the present day is presented as crisp, clean and polished, while the flashbacks to Taeko’s childhood is shown as hazy, dreamlike. These qualities give Takahata’s work a weight, realism and impressionistic feeling that is rarely found in animation, making him quite an unsung hero. Though he is retired due to Ghibli’s indefinite hiatus, he has left his mark on the medium, and should be looked at in the same level of respect as Miyazaki.

Honourable Mentions

I hope you have enjoyed my list. It has been an incredibly difficult task trying to choose just 5 directors given the large amount of brilliant creators that have worked in anime.In case you want to explore further, here’s a few who didn’t quite make the list but are all worth exploring:

- Koji Morimoto (Memories, Robot Carnival)

- Kunihiko Ikuhara (Revolutionary Girl Utena, Mawaru Penguindrum)

- Noburo Ishiguro (Legend of the Galactic Heroes, Space Battleship Yamato)

- Satoshi Kon (Perfect Blue, Tokyo Godfathers)

- Rintaro (Galaxy Express 999, Space Pirate Captain Harlock)

- Makoto Shinkai (Your Name, 5 Centimeters Per Second)

- Shinichiro Watanabe (Cowboy Bebop, Samurai Champloo)

- Junichi Sato (Princess Tutu, Aria)

- Ryutaro Nakamura (Kino’s Journey, Serial Experiments Lain)

- Sayo Yamamoto (Yuri on Ice, Lupin the Third: Woman Called Fujiko Mine)

- Katsuhiro Otomo (Akira, Neo Tokyo)

- Mamoru Hosoda (Summer Wars, The Girl Who Leapt Through Time)

Who would you say are your choices for favourite directors in anime? Are there any others who you think deserve more recognition? Leave a comment, I would be really interested to find out! 🙂